So jet lag thundered into my bones today but I made my 3 pm meeting with Dr. Stephanie Coane, at Eton College.

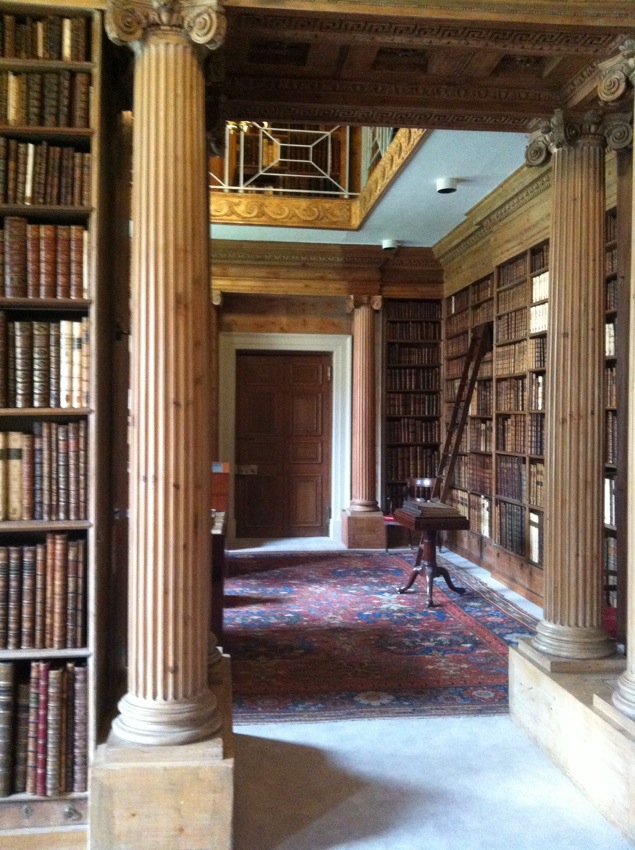

The library was exquisite. Raw wood. No oil, no varnish, no paint. It held such a soft armiture for the books to rest. It’s perhaps the gentlest library I’ve seen. The rooms had a quiet grace.

Apparently the College Library had 42 books in 1465. But the space I experienced was designed by Thomas Rowland and completed in 1725, when the library had 2 to 3 thousand volumes, with the capacity for ten times that number. They were looking to grow leaves.

Apparently the College Library had 42 books in 1465. But the space I experienced was designed by Thomas Rowland and completed in 1725, when the library had 2 to 3 thousand volumes, with the capacity for ten times that number. They were looking to grow leaves.

And between 1731 and 1792 five private collectors began donating works. Stephie elaborated on two: Richard Topham and Anthony Morris Storer.

Topham was a “grand tourist in Rome”. He collected drawings of antiquities of Rome that have since been lost or moved from Rome. And, as part of his agreement to donate, he required this previously restricted library to grant open access to scholars.

Anthony Morris Storer was an MP and bibliophile. His hobby was to buy books and “extra-illustrate” them — that is paste in cutouts. This is called “grangerizing” or “pennantizing” named after James Granger and Thomas Pennant. For example, Granger was the author of “A biographical history of England”, and Pennant wrote some account of London. With the illustrations added, theses books grow many times thicker on the shelf.

While I wasn’t allowed to photograph the contents of this box, it was filled with beautiful etchings of coins, individuals and coats of arms (many cut out of prior books as text was printed on their backs) all awaiting their proper re-position in some new book.

Stephie did her PhD in travel literature. So she shared a personal favorite called “Campi Phlegraei” or Fields of Fire, a book created by Sir William Hamilton in 1776, an English diplomat in Naples. Hamilton became obsessed with volcanos and his hobby was to watch Vesuvius which was very active in the 1770s. He climbed it 200 times! In reporting his observations to the Royal Society, he realized the letters themselves were insufficient, so he hired a monk to make continuous observations and an artist to make renderings! This book nearly bankrupted him but is gorgeous science that is apparently still used today.

Stephie did her PhD in travel literature. So she shared a personal favorite called “Campi Phlegraei” or Fields of Fire, a book created by Sir William Hamilton in 1776, an English diplomat in Naples. Hamilton became obsessed with volcanos and his hobby was to watch Vesuvius which was very active in the 1770s. He climbed it 200 times! In reporting his observations to the Royal Society, he realized the letters themselves were insufficient, so he hired a monk to make continuous observations and an artist to make renderings! This book nearly bankrupted him but is gorgeous science that is apparently still used today.

The images range from specimens to landscapes, written in English and French, and show the destructive power, the fertile landscape, and economic activity of volcano living. Stephie said one problem apparently discussed by natural philosophers at the time was the disagreement in the field between the neptunists and the volcanists- Was the source of the fire at the bottom or the top!? I do so adore how ideas can war so civilly on paper.

And I appreciated The point that image and letter both work better together than alone. If only I had time or energy, I would head to the British Museum and see sample rocks from these expeditions that relate to this book connecting time, place, and material reality.

In other notes, upon my arrival, I was told by the guard that Eton was the first boys school in England (though someone who read this post questioned this statement.).

The schoolroom was delightfully marred by the hands of many boys over time.

The schoolroom was delightfully marred by the hands of many boys over time.  Though, not myself Denny, I was oddly reminded of an Adrienne Rich poem “Hunger”: the passion to be inscribed her body.

Though, not myself Denny, I was oddly reminded of an Adrienne Rich poem “Hunger”: the passion to be inscribed her body.